The Fruits of Our Labour: An Interview with Tulapop Saenjaroen

An interview with Tulapop Saenjaroen on his latest film Mangosteen (2022), exploratory forms of storytelling, image-making and politics, and the relations between work, play, language and violence.

The cinema of Tulapop Saenjaroen changes shape unpredictably, film to film, and yet what running constant through all these speculations, play and collisions are the entwined concepts of work and play. For nearly two decades, Saenjaroen has probed the parasitical relationship that frequently exists between these concepts, which has festered under capitalism and accelerated in recent decades. With each year, work devours play under the mounting, global conditions of the erosion of the divide between rented and free time and the monetisation of recreation and creativity which fuels the self-care and leisure industries and the corporatisation of art.

With Saenjaroen's latest film, Mangosteen (2022), his approach changes again. Compared to his hyperactive and high definition Squish! (2021), his latest film would seem more tempered. And yet his experimentation hasn’t ceased, and the previous film’s sub and suprastrates of existentialism are not only carried over but bloom.

Shot on DV, the image is often glazed with a functional skin, familiar to anyone who has had to sit through corporate, workplace videos. Saenjaroen not only mimics this aesthetic of calculated neutrality but sharpens it into both an expression of alienation and a lithe tool of observation pointed at the particular textures and rhythms of industrial labor.

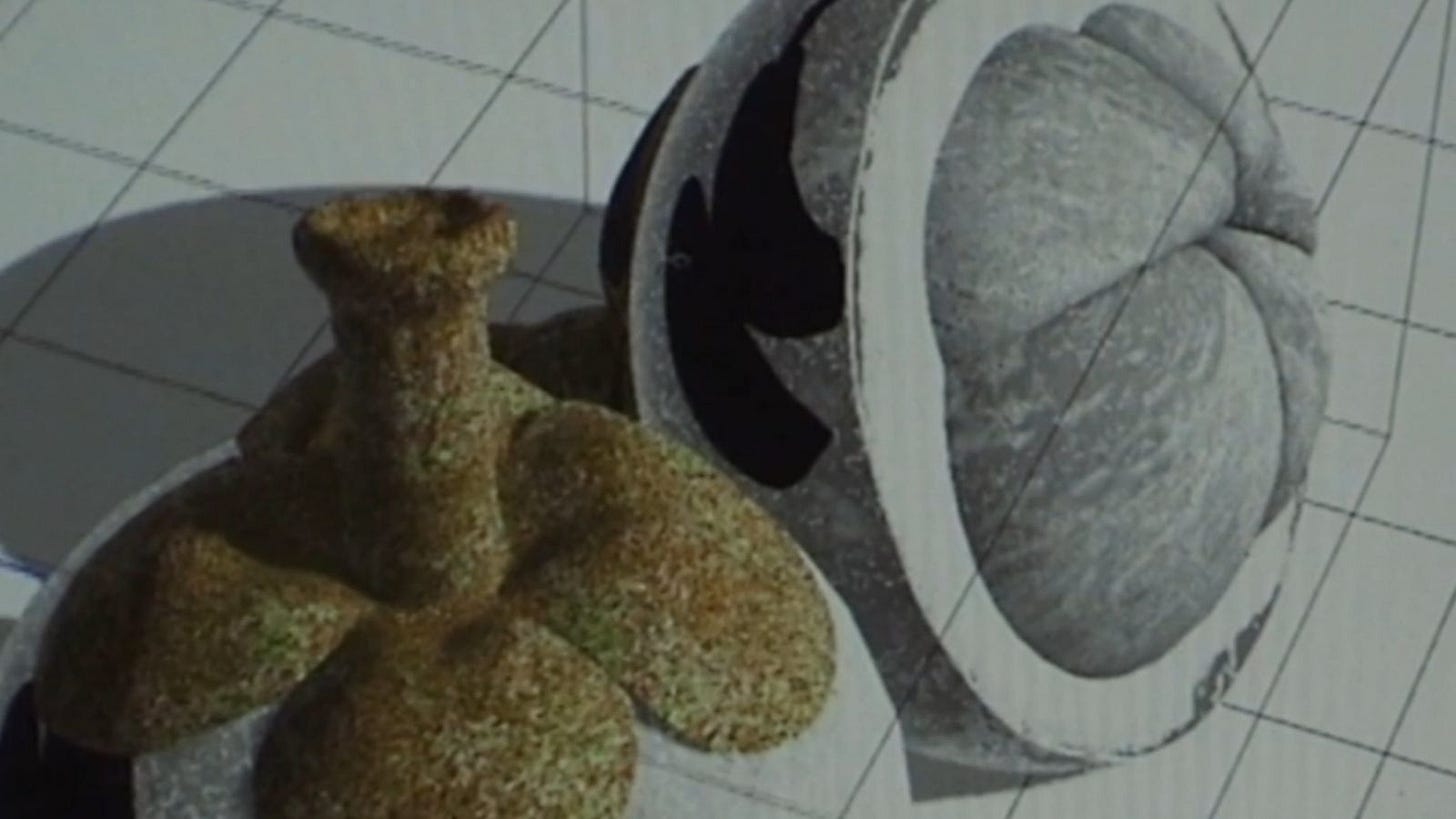

For the setting of Mangosteen is the workplace in the classical sense, the factory. Specifically, a mangosteen fruit juice processing plant in Thailand, which Saenjaroen depicts through a skein of locations and processes; the routine of cultivation and processing, rendered in a matter of fact but tactile way, to its public face, where labour in its complexity and more unglamorous aspects are elided and replaced with CGI icons and prancing costumed children.

Interlaced with this exploration of industrial process and aestheticization is a tale of familial, creative and existential turmoil. After an unsatisfying sabbatical, Earth (Saksit Khunkitti) returns to work at the factory underneath his sister and supervisor Ink (Prae Pupityastaporn). While she seems steadfast and secure in her station and thinking, he is somewhat of a lost soul. Inquisitive but unsure about his place in the factory, his life and his future. His insecurities grow when he gets into a disagreement with his sister, triggering an increasingly surreal, expansive and occasionally disturbing foray between the porous boundaries of work, self-worth, imagination and freedom.

Last Autumn, I communicated with Saenjaroen over email about the film’s improvisatory production, the relationship between capital and art, language and violence and images as a potential weapon against hierarchy and conformity.

Ruairí McCann: I think a good place to start with Mangosteen is with the setting of the juice factory. A lot of your work deals with depicting and delving into what feels like a very 21st century problem. How states of labor and leisure have become increasingly blurred and overlapped, in ways that could be revolutionary but most often work to the advantage of the capital class, who reappropriate and invade values and zones of creativity, pleasure and vulnerability in order to exploit them. Some of your recent films are set in contexts where these slippages and cross pollination often rise to the surface. I'm thinking of the hotel and automated tour of A Room with a Coconut View (2018) and the film shoot of People on Sunday (2020). However, with Mangosteen you're dealing with the classical paradigm of an industrial, production-oriented workplace which would seem to me to offer up different dynamics. I'm curious what interested you about making a film set in a factory?

Tulapop Saenjaroen: I often use the site of production as a main location, both physical and mental one, in most of my films, as I’m interested in investigating the construction, its agenda, and other possible involvements. When we shoot at the site of production, I hope to have a distance to see its process and, potentially, alternative ways of looking at it.

When I started thinking of the project Mangosteen, I also thought of a press fruit-juice factory. The juice factory has the specific qualities and the dynamics that I'm seeking for this particular film. It fascinates me to think of the process of disembodying, extracting, sanitizing, and transforming. The contrast of mangosteen’s body, its skin, its squishy fresh and its colors and the industrial looks and noises of the factory also inspires me to write about the power dynamics between flexibility, rigidity, and plasticity. And also because factories often connote mass production, I found it challenging to write scattered and peripheral stories in such a set-up.

I would like to ask you about the film's unpredictable, multiplying approach to narrative. It's a film that is certainly interested in depicting the details of the factory and its power dynamics yet runs according to a logic that feels playful and circuitous, rather than factory-made. Could you describe the process of developing the story (or stories)? Also I'm curious about the difficulty of writing peripheral stories in the context of mass production.

To me, fiction is often meticulously rational, seemingly more logical than reality sometimes. I often think of it as a question of control and freedom towards one’s subjectivity. For Mangosteen, I want to play with different sets of logics, rationalities, and perspectives—I guess I’m interested in the multiple crashes.

When we started the shoot, the script was only half finished. The process was to improvise with the location and performers/characters during the shooting days. I tried to find diverse ways to imagine the story/ies with the environment as a way to question and explore myself writing the story. We tend to shoot a lot whenever we can perceive any possible story from what’s going on in the shooting location (for example, some characters emerged during the shoot, or the purple robot dog). Sometimes, we did not even know whether what we shot would “fit” with the final film until the editing process. I guess I’m more comfortable with rooms to explore that are against the pre-written structure—not to prove or trying to depict any full picture of a story, if that ever exists, but to expand imaginability, to play with the power structure, to unlearn and reflex my own writing.

The choice of shooting on Digital8 video is striking. Occasionally, its qualities reminded me of the sort of informational or industrial videos made for the workplace. What motivated you to use this particular format?

Like before making any film, I ask myself what kind of look or which camera would fit with the film. And when I think of something then I will be curious why I think of it as a fit—do I think that way because it’s widely and repetitively used in a specific sense? For this film, I wanted the camera that is often being looked at as an aesthetic from the past while the story is somehow about the question of a future. Apart from the fluctuating meaning of the look, I also like the quality of the image, the gains and noise on the surface, and the fun zoom, haha.

I would like to talk about a specific, disturbing moment that emerged from this storytelling process. It's the scene where Earth describes how he wants to violently tear apart Ink. On the one hand, it appears to be a bitter, personal fantasy of revenge, on the other, Earth describes it calmly, as a radically transformative act for the good of both Ink and the other workers. Violence seems to be an often complex force in your work, as something blotted in the historical record and masked with cleaned-up representations but which manifests in the world of dreams and images. Could you tell me about this scene and your thoughts on depicting violence?

When I wrote the scene, I was trying to imagine what Earth is repressed from. He’s somehow struggling being with himself. He starts to feel the synapses between himself and his surroundings. He tries to use language as an outlet to generate thoughts that are not yet or possible to become an image. He wants to role-play and tries not to dichotomize rationality and irrationality. He’s having second thoughts about his own thinking. I think of this as a way for him to annihilate his former subjective constitution as well as a way for him to conceive new forms of thinking and perceiving—not really as an escape. For me, though quite abstract, violence often lies in the structure of framing, not only things we can imagine but also, especially, things that disable us to imagine.

I'm interested in this idea of the character Earth trying to use language to break out of his repression, only for it to land him in a state of violent confusion. In contrast, Ink seems to move beyond her own thought process, rather than get tangled up in it, when she suddenly starts speaking in German, a language previously unknown to her. Language as both a playing field for some sort of personal or creative evolution and as a prison features in several of your films. I'm also thinking of The Animation in Squish! (2021) and how it monologues its own painful but ecstatic metamorphosis. Could you talk about language as a creative force in your work?

I think maybe language is one of the closest frames for human conditions. Ink changed the language she speaks, wishing that she could be something else but ended up just becoming ‘someone else’. For me, language is just so close to rationality, arranging logics, translating/expressing feelings, making senses, ordering senses, etc. But it’s like a pharmakon, sometimes we use it but at times it uses us. I personally believe that moving-image has an ability to displace language to a different, slippery, freer environment—so it could be what it is and what it is not at the same time.

I feel that you're very attuned to how moving images are used to exploit a deeply human yearning for freedom by selling the concept wholesale in the shape of stop-gap products or lifestyles masquerading as breaks from an oppressive norm. Do you think moving images can truly play a role in planting and encouraging freedom in a true sense, politically or personally (or both inseparably), and not just as a commercialised placebo?

I want to believe that any medium has possibilities to plant and encourage a sense of freedom in various degrees, but if it’s in a true sense or not, that I don’t know (which I think it’s great to be constantly questioned). For me, it is more about how it is conceived, perceived, re-interpreted, reflected upon itself, and critically pushed. So I don’t think of it as a yes or no, or a one way communication, or a one way generator. As I believe that freedom is actualized through actions in relations, both the way the work participates in public and the way the public interact with the work are thus equally essential. For me, it’s not like granting or choosing from the already givens, but more of creating an open space.

If you would like to support my writing, please consider subscribing.