The Land of Saints, Sinners & Big Tom

On two shorts seen at Docs Ireland 2023: A mother's love for her baby & 2 Channel Land

Special thanks to Maximilien Luc Proctor for his help in editing this piece.

A mother’s love for her baby

Cat and Eímear McClay are two young artists with a relatively small body of work and yet have arrived at a metier that feels fully incarnated. In the span of three years, across a number of short films, exhibitions and single digital pieces, they have been practising an art of subversive, queer sanctification, akin to what can be found in shards across many online circles, but through the McClays it finds a more distilled and controlled form. Their films are hypnagogic drifts through Catholic holy places and objects, from the institutionalized (altars and sacrarium), the domestic (house shrines) and the secular (well-adorned bedrooms) along with the associated paraphernalia, from painted icons to hairbrushes. These tableaus and still lives are rendered in 3D animation which—with its slightly fuzzy textures, inelastic forms and limited frame rate in those rare moments of motion—is reminiscent of the first wave of 3D video games, for instance, Myst (1993). Therefore, their work occupies an ecstatic realism with familiar objects and scenes rendered in a tactile fashion, but given an atmosphere of antiquity, even alienness. The perspective veers between the neo-classicalism framing to close-up, still life views of objects which, to a brain conditioned by gaming, suggests the possibility of interaction. A beckoning to reach out and caress, rather than the signifying of a divinely inaccessible plane. It's work then that evokes the heavenly aura and presentation of Fra Angelico and catalogued casualness of Adrienne Salinger.

The thread of their work is a critique of the Catholic Church. How its reign in social and political spheres is cemented by a colonization of our unconsciousness, perpetrated through the pervasive control of taboo and images. In an interview with The Skinny, the McClays rooted their work in an adolescence spent in Ireland in the late 2010s and their awareness of the limits of that decade’s popular, secular overthrow of Church rule: with the eventual island-wide legalisation of abortion and equal marriage (in the South by popular vote ). In retrospect, it was clear to them that despite these legislative upheavals, that Catholicism’s dos and don’ts and the scars left on the minds of so many people, with women and queer people bearing the brunt, survived this transformation, internalized. If the Church then can freely expand behind their institutions and holy spaces, pervading every walk of life and nearly every public and private moment, then the films of McClays are a counter action, where said holy spaces are redecorated and so redefined

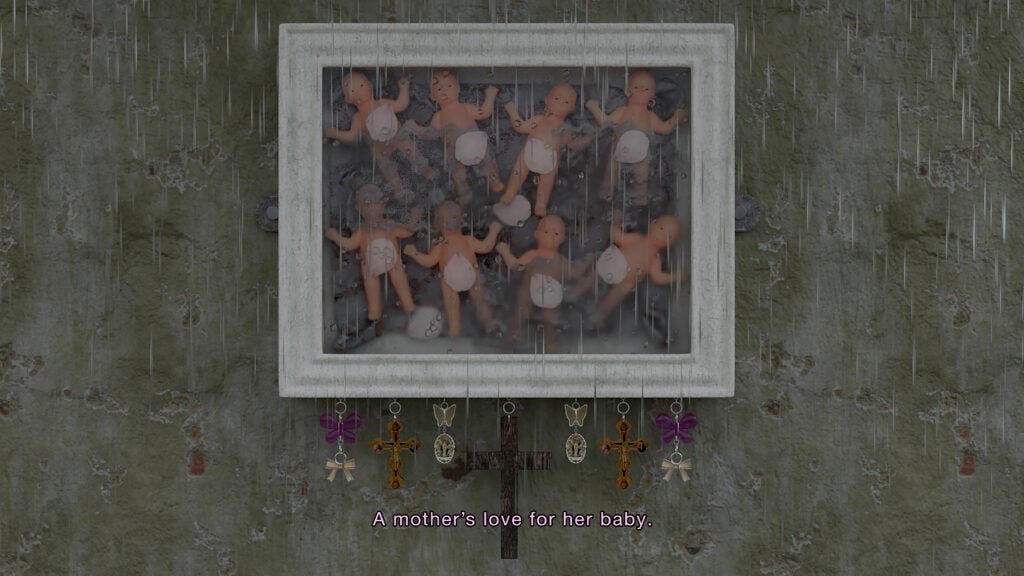

In their latest film, A mother’s love for her baby (2023), the critique is explicit. Its subject is the hushed-up malfeasances and buried bodies of Ireland’s institutions of entrenched, Church operated and anointed misogyny: the Mother & Baby Homes and Magdalene Laundries, told through a merging of their style with a poem by historian Catherine Corless, relayed through the use of subtitles. The intensive use of subtitling, not just as a tool of translation but as an active, aesthetic element in and of itself, has become a common element (or a fad, if one was to be less kind) in experimental cinema of recent years. In this case, it plays a powerful role in expressing both the violence and trauma of these ‘homes’ and their widespread cover-up. Corless’ poem starts with a hauntingly blunt evocation of the legacy of these homes, referencing the discovery of a mass grave of infants at the Tuam home with a disturbing catalogue of children’s bones. How all two hundred of them, scattered like refuse, once composed a living body but now exists as a faceless, shameful body of evidence. Eventually the poem moves onto the wrenching emotional, less corporeal just as visceral, aftershocks of the system and its oppressions.

All of this moves inexorably ahead in a ream of unspoken words. The silence mimicking a damning conspiracy of silence, enacted society-wide, across the entire island. Physical and psychological violence becomes the literal subtext of Catholicism, the backhand that you will receive if you reject, or even if you accept, the consolations of the Majer Magistra and her teachings. In concert with these subtitles, with the subtext of the Church laid bare, the film’s images, its ornate, flowing tapestry, takes on an abundance of meanings. Occasionally, it appears that the McClays are working on a highly ironic register, showing the carefully constructed appearance of divine beauty and order which the uncovered horrors bely. Other moments, reality, not the illusion, is made corporeal, with a cut to a rusty, rain-drenched fence or a floating dagger, a weapon of guilt, oppression or perhaps a popular, rather than deified, thrust for retribution.

2 Channel Land

It’s perhaps a little-known fact abroad, but American country music is massively popular in Ireland. It’s the case today and has been so for many decades, to a level that far outstrips the genre’s traction in Britain, in England especially, and I’m sure the rest of Europe. The popularity of ‘Country and Irish’—a cumbersome and perhaps overly imposed moniker for the phenomenon of Irish musicians taking on American country, which I will use for convenience but also since it acknowledges its commercial and hybrid qualities—was evident throughout the mid-20th century, showband after showband would play up and down the country on a circuit of ballrooms and church halls. If you jump to the present, there’s Garth Brooks’ slew of performances at Croke Park in 2022. He sold out the 80,000-seater venue five times over five successive nights to the tune of 28 million euro, with five more nights scheduled for this September. It’s a religion with a heady pantheon including Americans Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton to homegrown idols such as the late Big Tom, elder statesman Daniel O’Donnell and ageing upstarts such as Nathan Carter.

One interesting quality of the whole phenomenon is the contrast between its pervasiveness and how rarely it is seriously discussed. Many critics and traditional musicians see it as the pale, plastic art in comparison to Ireland’s own folk tradition. This is somewhat a line firmly drawn in the ever-shifting sand, since Irish folk is no pure object, incorporating over the years a range of foreign genres and instruments, such as the Scottish ballad, that Italian instrument of Arabic ancestry we call the violin and even the styles and instruments of American folk and country itself, which in turn is of partial Irish parentage. Culture moves like a bouncing ball rather than on a neat, straight line.

The source of this view, and generally the aspect of the Country and Irish which puts off many, is the strong, if not all-encompassing, twinned strands of crass commercialism and conservative messaging that run through it. The hard-bitten, bottom-up genre as described in Nick Tosches’ Country (1977) which provided the “twisted roots” of wave after wave of vital popular music, turned into shiny, soft, and toothless commodity, manufactured and enforced with the power of capital rather than up and through the folkways.

I made an online search for critical writings on the subject and did not turn up much, save for an interesting thesis posited by Stan Erraught, entitled ‘Country and Irish Problem’ and published in 2021. Erraught offers up a critique of Country and Irish as a popular form imposed on Ireland through a combination of colonialist, corporate and native, right-wing interests, framing the genre’s boom following the Second World War as an example of American hegemony’s economic and cultural imperialism, taking advantage of a general backlash in the South against British popular culture and fitting in with the both the Irish state’s and the unionist government’s competing attempts to broadcast and indoctrinate an image of the nascent republic or loyalist Ulster as the beating heartlands of Christian conservatism. Though the ‘licentiousness’ of popular music of all kinds would conflict with the dour Jansenism of mainstream Irish Catholicism and the puritanism of evangelicalism.

2 Channel Land (2022), directed by Frank Sweeney, treats Country and Irish specifically and mass culture in general not with an Adornoian dressing down or by embracing or throwing a blanket over any reactionary elements. Instead, it treats these forms as potentially grassroots and galvanising. It does so by diving into a malleability of interpretation which creates the tension between those denizens of corporate power which steals, packages, sells and claims ownership over art and the perspective of the majority who are meant to eat whatever they’re given. If the populist language hijacked by the former, such as advertising country as the people’s music or Marvel superheroes and films as our new gods and myths, were to be taken seriously than it would be unravel the buyer and seller dynamic on which their power is sourced. 2 Channel Land is an embodiment of that malleability as a short but sprawling palimpsest of ballads with an unpredictable form.

In contrast to the precise formalism of the McClays’ film, where the classical is hacked and recoded, Sweeney evokes pop culture as a kind of Frankenstein Monster, with a purposefully erratic, ‘pull the rug from under itself’ approach. It’s bookended by two real events, portrayed quite differently: through the warm, fuzzy haze of archival video we are treated to an account of a town in rural Cork in the ’80s who collectively, defiantly erected their own TV transmitter in order to receive signals from both Irish and UK stations, effectively dissolving the border between the north and south as it exists on the radio waves and creating one route to a shared culture. The film eventually ends in the present, with a free-roaming, digital camera following a decked-out, dancing cowgirl (dancer Janie Doherty) as she infiltrates one of Brooks’ mammoth Croke Park shows, allowing the film to yoink and re-contextualise this glistening capitalist spectacle.

In between, the film is glued together with a countrified Irish pastoral, depicted with an exaggeration of the parodic bucolic look of a Richie Kavanagh video. Doherty and singer-songwriter Lorraine McCauley sing ballads of cross-border exchange* dedicated to those intrepid, rebel broadcasters down in Cork and linking tunes and images of the South with those of the North. It reaches a zenith with Doherty and McCauley appearing as floating, crooning icons in the sky, like ad hoc guardian angels beamed into your living room. The tunes are not songs of praises for any authority, divine or earthbound, or offer an easily sellable or imposed idea of happiness and community delivered with a cracking, rictus grin. Their themes for film which imagines a popular art powered by the people and filled with rebellion and play.

- Ruairí McCann.

*A personal digression: it’s a genre that shows up even in my own family history. It starts in the Jazz age with my mother’s father’s side, the Ferrans of Dungannon. There’s my great-grandfather Jimmy Ferran, a drummer and a bandleader who played the ballrooms with a swing band that was practically a small orchestra, with around ten members. My grandfather Brian, or Granda Barney as we called him, was a bassist. He learned the ropes with his dad’s band and later played in the country outfit, Brendan Hughes and the Huskies, a live fixture of the Mid-Ulster scene in the 60s and 70s. In 1973, they even recorded a single, with a cut of ‘Irma Jackson’ by Merle Haggard as the A side and on the B Side, ‘I Washed My Hands in Muddy Water’ first sung by Stonewall Jackson and ‘The Lord Knows I'm Drinking’, a Cal Smith hit. You can listen to Irma Jackson here.

**It’s key that the cast are cross-border, Doherty is from Derry and McCauley from Inishowen.